Nuke Mars

- wp_7961204

- 0

- on Mar 13, 2024

Sabato 14 ottobre 2023 alle ore 18.00 la Galleria Mazzoli di Modena è lieta di presentare le mostre Filosofo di cipria. Rosa dietro di Vincenzo Cabiati e Nuke Mars di Marina Gasparini.

La mostra di Vincenzo Cabiati prende il titolo dalle due serie di opere ceramiche esposte in galleria. Filosofo di Cipria è composta da circa trenta opere in porcellana, realizzate nel periodo 2020-2022, in cui emerge un’iconografia che deriva e si ispira all’arte e al cinema: da Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, François Boucher, Eugène Delacroix e Giambattista Tiepolo a Peter Fischli e David Weiss, a Marie Antoinette di Sofia Coppola e Barry Lyndon di Stanley Kubrick. Il titolo della serie fa riferimento al pulviscolo creato durante la produzione della porcellana, trasformato nella mente dell’autore in una nuvola di cipria profumata che avvolge figure settecentesche. La serie Rosa dietro comprende quattordici piatti in terracotta invetriata, realizzati su forme originali del Seicento e smaltati sul retro di colore rosa. Questa caratteristica, da cui la serie prende il nome, infonde alle opere un’aura di sogno e leggerezza. All’interno della cornice barocca dei piatti, prendono vita scene e soggetti che si ispirano ai temi e all’arte del Barocco e del Romanticismo: da San Giorgio e il drago di Eugène Delacroix a Rubens e Antoon van Dyck. Le scene raffigurate non sono citazioni ma evocazioni, ‘appropriazioni’ attraverso cui Cabiati dà vita a personali interpretazioni e narrazioni in forma scultorea.

Irene Biolchini nel testo del catalogo specifica che “I due cicli presentati […] sono la fusione delle sue case e delle sue storie, senza però che questo degeneri mai in biografismo. Come l’ispirazione non degenera in citazione, allo stesso modo la vita non si riduce al biografico o all’evento”.

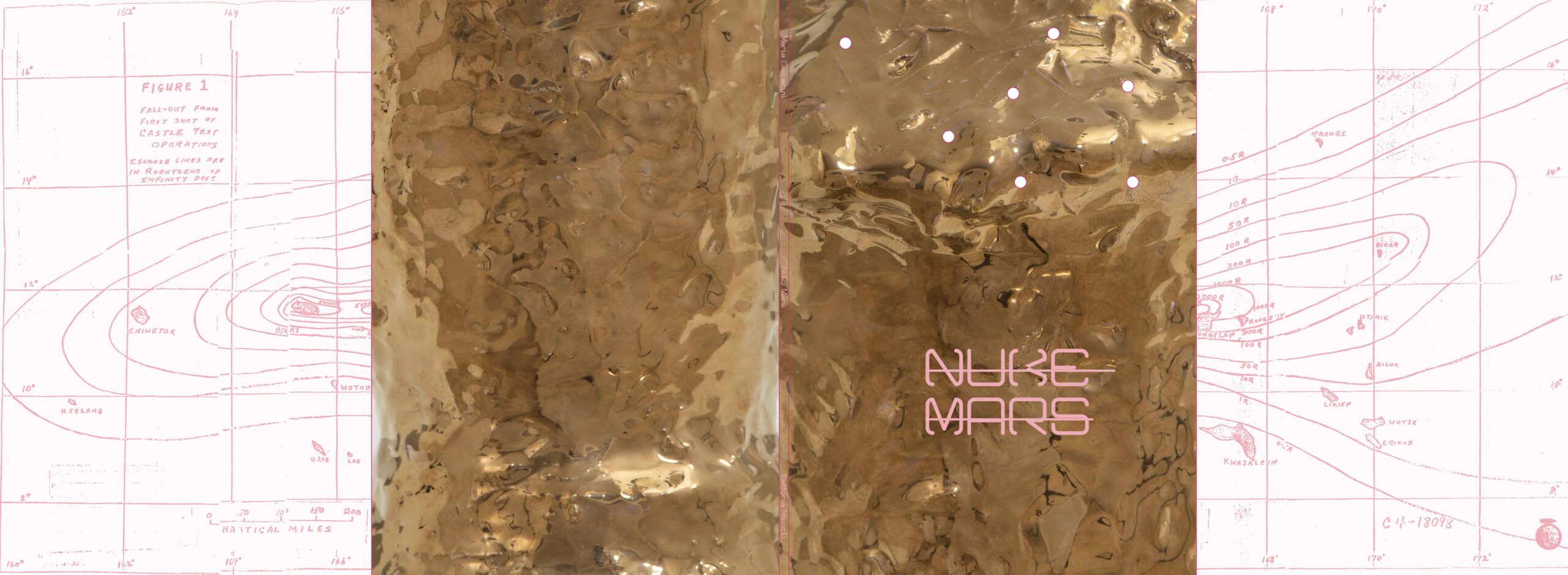

L’installazione di Marina Gasparini, Nuke Mars, composta da trentuno vasi-scultura policromi, è l’evoluzione di un suo precedente progetto intitolato Schiaparelli costituito da un gruppo di vasi in ceramica rivestiti di filo, le cui forme riproponevano un villaggio marziano apparso durante uno stato di trance alla medium Hélène Smith, celebre per la sua capacità di parlare e scrivere in linguaggi a lei sconosciuti. Il gruppo di ceramiche presentate in mostra è ispirato dal saggio Dalle Indie al pianeta Marte dello psichiatra Théodore Flournoy dedicato alla figura della medium e da altri testi riguardanti l’artista-sensitiva. Il progetto nasce durante un periodo di residenza artistica in un villaggio del Rajasthan affacciato su un deserto roccioso dalle sembianze marziane, caratterizzato dall’assenza di corsi d’acqua, e la cui unica attività artigianale è la ceramica. Il titolo dell’opera Nuke Mars, fa invece riferimento alle dichiarazioni di Elon Musk sulla volontà di bombardare con armi nucleari Marte con lo scopo di “nuclearizzare” il pianeta rosso per creare un’atmosfera simile a quella terrestre, realizzando finalmente il sogno di una sua colonizzazione da parte del genere umano.

In questo progetto per la Galleria Mazzoli, Marina Gasparini fa convergere nelle sue opere le attività primarie sia tessili che ceramiche che caratterizzano il sorgere di tutte le culture a tutte le latitudini, fino a formulare una pragmatica utopia di pseudo-architettura modulare.

L’esposizione è accompagnata dalla pubblicazione di due cataloghi: Vincenzo Cabiati – Filosofo di cipria. Rosa dietro con testo critico di Irene Biolchini, contributi di Stefano Graziani e Amedeo Martegani e fotografie di Stefano Graziani e Marina Gasparini Nuke Mars con testo di Roberto Terrosi.

Vincenzo Cabiati è nato a Vado Ligure (SV).

Si è formato nello studio del padre Achille, pittore che dagli anni Quaranta ha aderito al realismo e alla fine degli anni Ottanta si è trasferito dalla Liguria a Milano.

Nelle sue opere attinge a un variegato repertorio iconografico fatto di arte, cinema e architettura, da cui preleva frammenti significativi, astraendoli dal contesto originario e attribuendo loro un rinnovato valore poetico e affettivo. Utilizza una grande varietà di linguaggi: pittura, acquerello, disegno, scultura, fotografia, installazione, video. Negli ultimi anni la ceramica policroma rappresenta il mezzo privilegiato dell’artista. La sua ossessione per la sequenza e l’inquadratura fanno del cinema un’inesauribile fonte di immagini per le sue opere.

Ha esposto presso Villa delle Rose a Bologna, Museo della Ceramica di Savona, MASI e Museo Cantonale d’Arte di Lugano, Assab One, Studio Marconi, Galleria Massimo De Carlo di Milano, Galleria Mazzoli di Modena, Galleria Continua di San Gimignano, Museo Internazionale Design Ceramico, Laveno Mombello (VA), Certosa di San Lorenzo, Padula (SA), Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, Milano, FRAC Corsica e FRAC Montpellier, Francia.

Vive e lavora a Milano.

Marina Gasparini è nata a Gabicce Mare (PU).

Ha studiato all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Ravenna. L’uso dell’emblema visivo e l’utilizzo delle fibre tessili e della gestualità nel processo di realizzazione dell’opera, sono gli elementi fondativi della sua ricerca, sempre soggetta a continue riformulazioni in relazione alla progettualità prevalentemente site-specific. La sua pratica artistica si sviluppa partendo dalla rielaborazione di soggetti iconografici provenienti da epoche e culture diverse e da interessi culturali che attingono ad ambiti esoterici, botanici, letterari, scientifici ed etnografici in dialogo con lo spazio architettonico o geografico.

Ha partecipato a programmi di residenza artistica in Germania, Belgio, Rajasthan, Giappone, Stati Uniti, Finlandia. Nell’estate 2023 ha sviluppato un progetto di ricerca sull’impatto del colonialismo nelle collezioni etnografiche presso il Linden Museum di Stuttgart durante una residenza artistica nell’ambito del Progetto europeo Taking Care, Ethnographic and World Cultures Museums as Spaces of Care. Nel 2022 è stata vincitrice del premio “Sustainibility and Ars” organizzato e promosso da Laguna Prize con l’Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia e NaturaSi.

Vive e lavora a Bologna, dove è docente all’Accademia di Belle Arti.

Nuke Mars/Marx

by Roberto Terrosi

In a novel, this story would begin with a trip to India, or with certain statements uttered by the eccentric billionaire Elon Musk. Or not. Maybe it should start with the story of a Swiss medium who went into a trance. Or it could go back still further, to the 1700s, when Mesmer conducted his experiments on magnetism. But what is the relationship between all these things? What holds them together? What is the thread that crosses through and ties them to one another? And then, if we go back to read the title of the exhibition, we see that it is “Nuke Mars,” more or less the phrase spoken by Elon Musk on television: “I want to nuke Mars.” So in a certain sense the discussion centers on Mars and nuclear arms. We have thus introduced the themes of this episode. And we can go back to the time spent by our artist in India, for an art residency, invited there by a foundation. Marina Gasparini noticed the presence of a potters’ workshop, and she thought she might turn to them for the production of some pieces in ceramic. But what would be the subject? Now the scene shifts, and we find ourselves in fin de siècle Geneva, the place of residence of Catherine Élise Müller, who became known as Hélène Smith, where seances to summon spirits were much in vogue. Now from an anthropological and also psychological standpoint it is interesting to note that to make the contacted spirit speak, it was necessary to construct an impersonal dimension. How was this impersonal condition achieved? Usually in the seance it was obtained first of all through a collective action whose will could not be attributed to one person in particular; the other method, instead, was to rely on one particular person to act as a go-between with the afterlife, having the abilities of a medium. We are talking, then, about the trance. As Ioan Lewis correctly pointed out in his historic essay (Ecstatic Religion, 1971), these practices involved mostly women, especially in cultures with a strong patriarchal character, in which women undergo forms of both physical and psychological coercion and repression. In fact, one characteristic of the trance is desubjectivation, by which the medium can be exempted of responsibility for speech, just as in the symptom of hysteria the subject is exempted of responsibility for anything implied by that condition. In the moment in which the subjectivation of a woman, not being accompanied by any power, becomes a form of subjugating objectivation, the neurotic symptom or the trance become the ways to escape from this subjugation precisely by way of the objectivation itself, since the subject is acting as a simple body, or is activated by a spiritic presence by which it is possessed. Under this aspect, however, there is a significant difference between the somatic objectivization of the neurotic symptom and the psychic objectivization enacted by the spiritic presence. In the first case, reduced to a body it transforms any possible voluntary behavior into a natural contingency, which implies a medicalization of the symptom, in such a way that it is placed on the lowest rung of the social ladder, being a mere diseased body (naked life). Diversely, in channeling or trance the desubjectivation yields to a spirit of which the medium claims to be a simple megaphone, except for the fact that from its mouth an important voice is emitted, which has a power. Therefore in the trance the subjugated woman is not only exempted from responsibility for the words that come out of her mouth, but is also endowed with power. Catherine Élise Müller was born in 1861 in Martigny, but she grew up and went to school in Geneva. Her youth has been painstakingly examined and described by the Swiss psychologist Théodore Flournoy. She was the daughter of a Hungarian merchant and was therefore a “foreigner,” a status that has importance in the history of religions, also in relation to possession. Just consider the example of the Dionysian xenia (Marcello Massenzio, 1969), in which the maenads expressed a form of feminine ecstasy through wine, which dissolves the person as a social structure, in a society where women were substantially imprisoned in the home, in a condition of gender segregation. Catherine too stated that she felt like a prisoner. It is also interesting to note that her father was an amazing polyglot, and that as a child Catherine indulged in glossolalia (speaking in an invented language), imitating the languages spoken by her father. Catherine loved those languages but did not have the patience to learn them, just as she lacked the patience for study, so much so that she was left back in school. Perhaps Catherine nurtured a sense of social compensation, with respect to her xenia and her poor scholastic performance. Perhaps she was seeking a shortcut to success. In the family it was her mother who was interested in the supernatural, having had visions, confirming the female prevalence in such phenomena. When Catherine began to take part in the seances she gained immediate results, and in fact the number of participants in the group doubled. She had been waiting for this opportunity. The year was 1892, one year after the death of Helena Blavatsky, leader of the Theosophy movement, and Catherine borrowed her name, becoming Hélène. With respect to female trances as a reaction to submission, it is symptomatic that she claimed to be the reincarnation of aristocratic women like Marie Antoinette or a Hindu princess, but the spirits that spoke in her trances were always important men. Victor Hugo was her first spirit guide, but he was followed by a certain Leopold, who then turned out to be Cagliostro. At a certain point she made contact with Martians, who explained their language, and she saw Mars. The India of the Hindu princess was a land of theories on reincarnation propagated by Blavatsky, but also an exotic place, a heterotopia, an outside, like her father’s homeland. This outside became utopian with Mars. The city of the Martians is a sort of Atlantis, with spires and gardens. She drew this city, and added a language of her own invention. This was thus a return to glossolalia, but in written form. Théodore Flournoy published his book on Hélène in 1900, the same year as Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams. Flournoy was renowned, and in fact Jung, in the introduction to the English edition, states that he relied on Flournoy to make a break with Freud. The book became a classic of psychology, and it could not escape the attention of Breton. It is possible that the “alien” panoramas depicted by Tanguy or Ernst were not immune to Hélène’s influence. Nevertheless, the book was later forgotten, as were the Martian vistas of Hélène Smith. In Italy it was practically unknown. It was not published until 2016, by Castelvecchi. Hélène thus returned to circulate in Italian artistic circles. Furthermore, her drawings were shown in 2022, in the central pavilion of the Venice Biennale. Hélène thus reappeared in the world of art, where she had been placed by the Surrealists.

Hence, as in a film, we return to the opening scene in which Marina is in India, like a sort of Hindu reincarnation of Hélène, and is reminded of her, making works inspired by the world of Mars. A circle thus comes to a close, but our story does not. Because there is still another circle to be closed, that of Elon Musk who goes on television to say that Mars should be bombed. Why was Hélène interested in Mars? In the years when Hélène was beginning her career as a medium, Schiaparelli published his theses on Martian canals that changed and re-formed, gaining international attention. In the English translation, however, there was a problem: the Italian term “canale” can be translated as “channel” but also as “canal”; the overly literal translation with “canal” would indicate artificial waterways. English-language readers thus had the impression that Schiapparelli had seen artificial canals on Mars, implying that a civilization existed there. This led to the widespread idea of the Martians, which survived until the time of the famous radio drama by Orson Welles, The War of the Worlds, which triggered reactions of panic when listeners believed there was truly a Martian attack in progress. This was in 1938. Orson Wells said: “the extent of our American lunatic fringe had been underestimated.” But only one year later, quite another lunacy was unloosed, with the outbreak of World War II. All the powers spoke of peace after World War I, but they knew it would not last, because – as Keynes clearly understood in The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919) – it was too humiliating. Therefore all the powers prepared for war, and war it was. Many dreamt of a final weapon, as Goebbels said, a Wunderwaffen, an astonishing weapon, but it was built in America, by a group of scientists led by Oppenheimer. With a useless but dramatic massacre of civilians, that weapon put an end to the worldwide conflict. The world entered the atomic age, in which the new enemy was Russia, not only because that country was the old geopolitical adversary of the British Empire, in an opposition between an imperialism of the nomos of the land with respect to the English nomos of the sea, but because Russia was the guiding force of world communism. The new war was systemic, based on class struggle, capitalists against labor force, bourgeoisie against proletariat. Red was the color of the Marxist planet, so in science fiction the red planet became the planet of communism, and the invasion of the Martians was confused with the invasion of the Marxians. During the 1950s many science fiction films were produced, based on the red planet and its terrible invasions that regularly threatened to bring about the end of the world. The anxiety generated by the Cold War was no longer the sadness over the end of a world: that of the aristocracy. What was at stake was not the end of a world, but the end of the world, the apocalypse. The theme of apocalypse was addressed by Ernesto De Martino in his last book, The End of the World (1977), where he speaks of the crisis of presence. De Martino also analyzed a phenomenon of possession that survived in the folk traditions of southern Italy: tarantism, which once again had to do with the female gender, inside oppressive rural patriarchal societies. But De Martino points to a conception that goes beyond the methodological individualism of depth psychology. He avoids falling into the trap of bourgeois individualism, and instead takes the perspective of agents interested in a common world, a Mitsein that always threatens to collapse through dehistorification, and thus the loss of sense of the future, therefore requiring support through acts of reparation. The trance, then, is not only an individual crisis but also a reparatory act to sustain a common world. In it the medium follows personal but also communitarian dynamics. The fact that the society fin de siècle needed the medium should be seen in relation to the Spenglerian sense of threat for western civilization that was sensed by the European intelligentsia. The visions of the red planet thus express the search for a world alternative to planet Earth.

America saw the red planet as a threat to its dominion, while on the other hand, in Russia, there was a different tradition. In revolutionary Russia we find two science fiction novels. One presents a negative view of Mars, but due to its interpretation in mythological terms, linked to the god of war. The title of the novel is Aėlita, by Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy, whom we should not confuse with Lev Tolstoy. The Martian society is portrayed as militaristic and dictatorial. The protagonist falls in love with the icy and beautiful Martian and martial queen Aėlita, only to realize thanks to a faithful friend that she is a merciless dictator. He revolts against her and persuades the populace to do the same. The novel published in 1922 prescient warning against the seduction of militarism. The other novel is from 1906 and is titled Red Star. Now it is all too clear that the red star is the symbol of the socialist revolutionary forces. The intent of propaganda is thus evident straight from the title. In this book the hero discovers that on Mars there is an egalitarian, peaceful and collectivist society. In short, a true utopia, somewhat similar to the one imagined by Hélène Smith. This image of a collectivist society jibes perfectly with the American nightmare of the red menace. Therefore it is easy to understand that Mars could represent a dream for a people that had suffered from exploitation and submission, while it could also be a nightmare for others, i.e. for a dominant, conquering nation.

Marina Gasparini, however, tells me about another particular factor. She began to think of Mars as the crossroads of many different but connected metaphors, already prior to her trip to India. Marina wanted to do an exhibition at the “Bagni di Mario” in Bologna, a 16th-century cistern now without water, a deserted panorama that is a bit “after the bomb.” This was precisely in a moment in which the news media were informing us that Mars was once a planet with water on its surface, like the Earth. This water is said to have evaporated, in part, while the remaining part survives in an enormous area of permafrost, especially beneath the polar caps. If Mars could once have been the metaphor of the communist social utopia, now that the planet has been reduced to a great desert this utopia itself has been desertified. And this consideration is particularly pertinent to Bologna, which was once the red star of Italian communism, and has now been reduced to an arid patch of ground, like the red planet. So we have reached a clarification of the implications of the vision of Mars as a political metaphor, but we have forgotten about Elon Musk. Elon Musk can certainly not be counted amongst the ranks of Marxist Marsophiles, nor among those of liberalist Marsophobes. He is definitely light years away from Marxism, having expressed Trumpian sympathies, though we also know that Elon Musk – like other billionaires – has leanings towards a philosophy known as “longtermism,” and its sphere of ethical reference known as “effective altruism.” In particular, Musk is interested in the idea that over the long term the ecological crisis can imply an existential risk for humankind. Tracing back, if the Decadents sensed the disquiet for the fall of western civilization under the pressure of the industrial revolution, and if from the 1950s onward mass society has expressed its anxiety about the thread of nuclear Armageddon, today the situation has not improved. In fact, today there is not simply the fear caused by climate change and artificial intelligence, but also the fear of the end of western civilization, joined in recent times by the fear of nuclear catastrophe. If we do not understand the long-term concerns of this thinking, we cannot grasp the deeper reasons behind Musk’s interest in Mars. Musk addresses many of these concerns, though not all of them. Thus the problem arises of working on an escape plan, or at least a plan B, so as not to succumb to possible disastrous outcomes. In science fiction literature there is by now even a familiarity with the idea of great spaceships plying the stellar reaches with a cargo of hibernating human beings, ready to reawaken after endless voyages in outer space. Nevertheless, for some time now science fiction has given up on the hypothesis of mass migration to neighboring planets. Also because space exploration has removed the credibility of all hypotheses of nearby planets that could be easily colonized. No one still believes that the canals on Mars were built by Martians, although those seeking archeological evidence of a very ancient Martian civilization thought to have escaped from their planet – which was once blue, and then began to dry up – reaching the Earth and giving rise to human history, have not totally vanished. They say the previously abundant water evaporated to a great extent, though some of it is still trapped in the permafrost, especially at the poles. At this point Musk comes along with the idea of sending nuclear bombs to melt the ice under the poles and to trigger a chain reaction that would even restore an atmosphere on Mars resembling that of the Earth. Today the temperature on Mars is very low, but at the equator it can reach 25 degrees Celsius during the day, and this means that the creation of a greenhouse effect would also make the nights milder. In short, after the bombing the red planet would return to being blue, as it is imagined to have been once upon a time in the past. The atmospheric pressure would also rise, though it would still be far lower than that of Earth. So the dream of making Mars inhabitable is very strong, and the business strategies to set it in motion emphasize all the positive possibilities, however insufficient and scarcely probable they may be. In many case, technological and scientific projects feed on aspects and emotional drives that may even be unconscious, and are far from being rational. Tesla, the “wizard” of electricity who became the inspiration for Elon Musk’s visionary rise and enterprise, said that he talked with Martians or Venusians via radio. Actually, it can well be assumed that this was a phenomenon of psychophony, known in English as EVP, which stands for Electronic Voice Phenomenon, familiar to scholars of the paranormal but also to psychiatrists. With Hélène Smith, Tesla shared the taste for pareidolia, which is the tendency to see forms in things without form, or for apophenia, a similar phenomenon that consists in attributing familiar perceptional schemes to random, unrelated elements, constructed connections where none actually exists. We can say that pareidolia has to do with an aesthetic inclination, and apophenia with a more theoretical bent, to the extent that it is more directed towards gnoseology. The point is that these are not just deviant inclinations of brilliant but unstable personalities like Nikola Tesla; they are the basement levels of rationality, in which it mingles with the irrational and even the fantastic, not to mention delirium. They punctuate the history of scientific thought, and it is worth recalling that science emerges from the mists of astrology, magic and alchemy. If we read the Renaissance naturalists such as Bernardino Telesio, who believed that nature should be studied iuxta propria principia and was speaking a few decades before the theories of Galileo, we can see that there is still much that is magical or alchemical in his conception of nature. The same is true of Giordano Bruno, a contemporary of Galileo (they lived for a period at a distance of just a few kilometers, and could also have crossed paths in the city of Venice). After all, even Galileo was not above offering his services as an astrologer, writing horoscopes for a fee. Isaac Newton practiced alchemy and was hired by the Royal Mint as an expert on gold. We are told about science as it emerged from the mists of such doctrines, after which it was able to break free. The history of science, however, narrates another truth: irrationality has never ceased to nip at the heels of science, and to mingle with it. After alchemy, in fact, came the studies on electricity. Electricity was perceived as a sort of magical fluid, sometimes invisible, sometimes visible in luminous phenomena, which could pass through bodies. Prodigious demonstrations of electroluminescence were produced, arriving at Tesla himself and his performances using his own body to illustrate phenomena of electrical induction. Tesla’s personality stands out in this cultural background of contamination and lack of distinction between scientific practices and magical paranormal wonders. We can also consider the idea of bringing dead bodies back to life which forms the basis of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, written with reference to theories that were in circulation at the time. The cliché of the mad scientist also emerges from this boundary between science and the irrational. In the case of magnetism, this aspect is even more pronounced. Just consider Franz Anton Mesmer and the mesmerism that bears his name, which was so widespread in the world of occultism that still in Italy, during the last century, during seances the medium was often called “la magnetizzata.” It is said that Mesmer was criticized by the scientific community, yet still in the 19th century the natural world was perceived as being laden with mystical, spiritual and irrational elements that had been discussed by the naturalists of the Renaissance. With Romanticism Naturphilosophie spread among the finest minds of German philosophy like Schelling and Schopenhauer, a philosophy of nature that mixed scientific, spiritualist and mystical claims regarding nature itself. Finally, radioactivity made inroads in the midst of bizarre theories and imaginative fascinations, such as those connected with the use of X-rays, linked again in this case with the circles of Theosophy. Röntgen himself called these rays “X” because they were mysterious and he knew not how to define them.

In conclusion, we can infer two positions that intertwine in this metaphor of bombing Mars and its imaginative but also metaphysical civilization, evoked by the ceramics which in turn refer to the drawings of Hélène Smith. The first reminds us that we are suspended in the face of the thematics of the end, the crisis, the apocalypse, in a dimension where science is unable to break free of its intertwining with the irrational. The second, instead, is more ironic and political, and seems to suggest the idea that perhaps the red planet of politics, once rich in waters and now arid, might be in need of a bombing to make its waters hidden in the ice return, bringing life with them. For this to happen, a psychic and visionary attitude is required, capable of again indicating utopian cities, from which the Martians/Marxians can go back to speaking their futuristic language. In a certain sense, we might say “Nuke Marx,” not to destroy him but, to the contrary, to bring him back to life. However one sees it, the work of Marina Gasparini is not limited to ceramics, because these ceramic pieces are like the diodes of a thinking machine full of inputs and considerations, re-elaborating the work itself as a machine for thinking, or even more so for meditating on these difficult times, in our time.

Nuke Mars/Marx

Se fosse un romanzo, questa storia comincerebbe con un viaggio in India, oppure con alcune dichiarazioni dell’eccentrico miliardario Elon Musk. Oppure no, dovrebbe cominciare con la storia di una sensitiva svizzera che andava in trance, oppure si potrebbe andare ancora indietro, al Settecento, quando Mesmer conduceva i suoi esperimenti sul magnetismo. Ma che rapporto hanno tutte queste cose tra loro? Che cosa le unisce? Qual è il filo del discorso che le attraversa e le cuce insieme? E poi se torniamo a leggere il titolo della mostra vediamo che esso è “Nuke Mars”, più o meno la frase pronunciata da Elon Musk, che in televisione ha detto: “I want to nuke Mars”. Allora in un certo senso il discorso ruota intorno a Marte e al nucleare. Abbiamo così introdotto i temi di questa vicenda. Possiamo allora tornare alla permanenza in India della nostra artista, per una residenza artistica, su invito di una fondazione. Marina Gasparini ha notato la presenza di una bottega di ceramisti e ha pensato che avrebbe potuto rivolgersi a loro per la produzione di alcune ceramiche, ma con quale soggetto? Cambiamo allora scena perché andiamo a trovarci nella Ginevra fin du siecle in cui vive Catherine Élise Müller, che poi diverrà nota come Hélène Smith, e in cui vanno di moda le sedute spiritiche in cui vengono evocati degli spiriti. Ora, da un punto di vista antropologico e anche psicologico, è interessante notare che per far parlare lo spirito evocato è necessario costituire una dimensione impersonale. Come si ottiene questa impersonalità? In genere nella seduta spiritica, si ottiene in primo luogo attraverso un’azione collettiva la cui volontarietà non può essere imputata ad alcuno in particolare; l’altra maniera è invece quella di ricorrere a una persona in particolare che fa da tramite con l’aldilà per le sue capacità medianiche. Parliamo cioè della trance. Come notava giustamente Ioan Lewis in un suo storico saggio (Le religioni estatiche, tr.it. Roma, 1978) queste pratiche riguardano soprattutto le donne, specialmente in culture con una forte connotazione patriarcale, in cui la donna subisce forme di costrizione e di repressione sia fisiche che psicologiche. Infatti, una caratteristica della trance è la desoggettivazione, per cui la medium può sottrarsi alla responsabilità della parola, così come nel sintomo isterico essa si sottrae alla responsabilità di tutto ciò che tale sintomo implica. Nel momento in cui la soggettivazione di una donna, non essendo accompagnata da alcun potere diviene una forma di oggettivazione assoggettante, il sintomo nevrotico o la trance divengono modi di evadere da questo assoggettamento proprio per il tramite dell’oggettivazione stessa, dal momento che essa agisce in quanto semplice corpo, o è agita da una presenza spiritica da cui è invasata. C’è però sotto questo aspetto una significativa differenza tra l’oggettivazione somatica del sintomo nevrotico e l’oggettivazione psichica operata dalla presenza spiritica. Nel primo caso essa, riducendosi a corpo, trasforma ogni possibile comportamento volontario in una contingenza naturale, che comporta una medicalizzazione del sintomo, in modo tale che essa si pone al gradino più basso della gerarchia sociale in quanto mero corpo malato (nuda vita). Diversamente nel channeling o nella trance, la desoggettivazione cede il posto a uno spirito di cui la medium pretende di essere un semplice megafono, fatto salvo però il fatto che dalla sua bocca esce una voce importante che ha un potere. Quindi nella trance la donna assoggettata, non solo si deresponsabilizza rispetto alle parole che escono dalla sua bocca, ma si carica anche di potere. Catherine Élise Müller nasce nel 1861 a Martigny, ma cresce e compie i suoi studi a Ginevra. La sua giovinezza è stata vagliata e descritta minuziosamente dallo psicologo svizzero Théodore Flournoy. Era figlia di un commerciante ungherese ed era quindi una “straniera”, condizione questa che ha importanza nella storia delle religioni, anche in relazione alla possessione. Si pensi ad esempio alla xenia dionisiaca (Marcello Massenzio, 1969) in cui le baccanti esprimono una forma di estasi femminile tramite il vino che ne scioglie la persona come struttura sociale in una società, in cui la donna è sostanzialmente reclusa o imprigionata in casa, in una condizione di segregazione di genere. Anche Catherine dichiarava di sentirsi imprigionata. E’ anche interessante che il padre fosse uno stupefacente poliglotta e che Catherine da bambina indulgesse nella glossolalia (parlare una lingua inventata) imitando le lingue parlate dal padre. Catherine amava, ma non aveva la pazienza di apprenderle, così come non aveva la pazienza di studiare, tanto che fu rimandata a scuola. Forse Catherine nutriva un senso di rivalsa sociale sia per la sua xenia sia per i suoi insuccessi scolastici. Forse era in cerca di una scorciatoia per il successo. In famiglia era la madre ad interessarsi al soprannaturale avendo avuto delle visioni, cosa che conferma la preminenza femminile di questi fenomeni. Quando Catherine comincia a partecipare alle sedute spiritiche ha subito successo, tanto che le partecipanti al gruppo raddoppiano. Era l’occasione che stava aspettando. Era il 1892, un anno dopo la morte di Helena Blavatsky, leader del movimanto teosofico, di cui Catherine riprese il nome diventando Hélène. Rispetto alla trance femminile come reazione alla sottomissione è sintomatico che lei dichiara di essere la reincarnazione di aristocratiche come Maria Antonietta o una principessa Hindu, ma nella trance sono sempre spiriti maschili importanti a parlare. Victor Hugo è il suo primo spirito guida ma poi arriva un tale Leopold che poi si rivelerà essere Cagliostro. Ma a un certo punto entra in contatto con dei marziani, che le spiegano il loro linguaggio e lei vede Marte. L’India della principessa hindu era patria delle teorie sulla reincarnazione sfoggiate dalla Blavatsky, ma a anche un luogo esotico, un’eterotopia, un fuori, come la patria paterna. Questo fuori diventa utopico con Marte. La città dei marziani è una specie di Atlantide, con guglie e giardini. Lei disegna questa città e vi aggiunge una lingua di sua invenzione. Si torna così alla glossolalia ma in forma scritta. Théodore Flournoy pubblicò il libro su Hélène nel 1900. lo stesso anno dell’Interpretazione dei sogni di Freud. Flournoy era rinomato, tanto che Jung, nell’introduzione dell’edizione inglese, racconta che si appoggiò a Flournoy per rompere con Freud. Il suo libro divenne un classico della psicologia, e non poteva sfuggire a Breton. È possibile che i panorami “alieni” dipinti da Tanguy o da Ernst non siano immuni dall’influsso di Hélène. Tuttavia il libro cadde poi nell’oblio e con esso anche i panorami marziani di Hélène Smith. In Italia era pressoché sconoosciuto. È stato pubblicato solo nel 2016 dalla Castelvecchi. Hélène è così tornata a circolare negli ambienti artistici italiani. Inoltre, nel 2022, alla Biennale di Venezia nel Padiglione Centrale si espongono i suoi disegni. Hélène così ritorna nell’alveo dell’arte in cui l’avevano posta i surrealisti. E allora torniamo come in un film alla scena di partenza in cui Marina in India come una sorta di reincarnazione Hindu di Hélène ripensa a lei per delle opere ispirate al mondo di Marte. Un cerchio si chiude ma non si chiude così la nostra storia. Perché resta un altro cerchio da chiudere, quello di Elon Musk che va in televisione a dire che bisogna bombardare Marte. Che ragione aveva Hélène di interessarsi a Marte? Negli anni in cui Hélène cominciava la sua carriera di medium, Schiaparelli pubblicava le sue tesi sui canali di Marte che cambiavano e si riformavano, destando l’attenzione internazionale. Nella traduzione inglese però ci fu un problema: il termine italiano “canale”, che può essere tradotto sia con “channel”, che con “canal”, venne tradotto troppo letteralmente con “canal”, che indica i canali artificiali. Questo suggerì ai lettori di lingua inglese che Schiapparelli aveva visto canali artificiali su Marte e che dunque vi fosse una civiltà. Da qui venne la popolare idea dei marziani che sopravvisse fino ai tempi della celebre trasmissione radio di Orson Welles, La guerra dei mondi, in cui della gente si riversò nelle strade credendo che fosse realmente in corso un attacco marziano. Era il 1938. Orson Wells disse: “Avevamo sottovalutato l’estensione della vena di follia della nostra America”. Ma solo un anno più tardi ben altra follia doveva sprigionarsi con lo scoppio della seconda guerra mondiale. Tutte le potenze parlavano di pace dopo la Prima guerra mondiale ma sapevano che non sarebbe durata, perché, come capì benissimo Keynes in Le conseguenze economiche della pace (1919) era troppo umiliante. Così tutte le potenze si preparavano alla guerra e guerra fu. Molti sognavano un’arma finale, come disse Goebbels, una Wunderwaffen, un’arma sbalorditiva, ma fu costruita in America, da un gruppo di scienziati diretto da Oppenheimer. Quell’arma siglò con un’inutile ma scenografica strage di civili la fine del conflitto mondiale. Sì entrava così nell’era atomica in cui il nuovo nemico era la Russia, non solo perché era il vecchio nemico geopolitico dell’impero inglese, che contrapponeva un imperialismo del nomos della terra rispetto a quello inglese del nomos del mare, ma perché era la guida del comunismo mondiale. La nuova guerra era una guerra di sistema fondata sulla lotta di classe, capitalisti contro forza lavoro, borghesi contro proletariato. Rosso era il colore del pianeta marxista, e così nella fantascienza il pianeta rosso divenne il pianeta comunismo e l’invasione dei marziani veniva confusa con l’invasione dei marxiani. Negli anni ‘50 si assiste a tutta una produzione di film di fantascienza basati sul pianeta rosso e sulle sue terribili invasioni che minacciavano puntualmente la fine del mondo. L’ansia suscitata dalla guerra fredda, non è più la malinconia per la fine di un mondo: quello dell’aristocrazia. In gioco non c’è più la fine di un mondo bensì la fine del mondo, l’apocalisse. Al tema dell’apocalisse Ernesto De Martino, dedicò il suo ultimo libro La fine del mondo (1977), dove parlò di crisi della presenza. De Martino inoltre analizzò anche un fenomeno di possessione che resisteva nelle tradizioni folkloriche del meridione italiano: il tarantismo e che riguardava ancora una volta il femminile, considerato all’interno di oppressive società patriarcali rurali. Ma De Martino prospetta una concezione che va oltre l’individualismo metodologico della psicologia del profondo. De Martino non cade nella trappola dell’individualismo borghese e invece si pone nella prospettiva di attori che si interessano a un mondo comune, in un Mitsein che minaccia sempre di crollare attraverso la destorificazione e cioè la perdita di senso del divenire, e che deve perciò essere sempre puntellato attraverso atti riparatori. La trance allora non è solo una crisi individuale ma un atto riparatorio per sostenere un mondo comune. In essa la medium segue dinamiche personali ma anche comunitarie. Il fatto che la società fin du siècle avesse tanto bisogno di medium va messo in relazione allo spengleriano senso di minaccia per la stessa civiltà occidentale che veniva avvertita dall’intellighenzia europea. Le visioni del pianeta rosso dunque esprimono una ricerca di un mondo alternativo all pianeta Terra.

L’America vedeva nel pianeta rosso una minaccia al proprio dominio, dall’altra parte in Russia invece c’era una tradizione diversa. Nella Russia rivoluzionaria troviamo due romanzi di fantascienza. Uno prospetta una visione negativa di Marte, ma a causa della sua lettura in chiave mitologica legata al dio della guerra. Il titolo del romanzo è Aėlita di Aleksej Nikolaevič Tolstoj, da non confondere però con Lev Tolstoj. La società marziana viene vista come militarista e dittatoriale. Il protagonista s’innamora dell’algida e bella regina marziana e marziale Aėlita salvo accorgersi, grazie al suo fedele amico, che lei è una spietata dittatrice e allora si rivolta contro di lei e spinge anche la popolazione a rivoltarsi. Il romanzo pubblicato nel 1922 è un preveggente monito contro la seduzione del militarismo. L’altro romanzo è del 1906 e s’intitola La stella rossa. Ora, è fin troppo chiaro, che la stella rossa è il simbolo delle armate rivoluzionarie socialiste. E quindi l’intento propagandistico appare chiaro fin dal titolo. In questo libro il nostro eroe scopre che su Marte c’è una società egualitaria, pacifica e collettivista. Insomma si tratta di una vera e propria utopia, un po’ simile a quella immaginata da Hélène Smith. Questa immagine della società collettivista si incastra perfettamente con l’incubo americano la minaccia rossa. Quindi si capisce bene come Marte potesse rappresentare un sogno per un popolo che ha patito lo sfruttamento e la sottomissione e potesse invece essere un incubo per gli altri e cioè per un popolo padrone e vincente.

Marina Gasparini però mi ha raccontato anche un altro particolare. Lei cominciò a pensare a Marte come crocevia di tante metafore diverse ma connesse, già da prima del suo viaggio in India. Marina pensava già di fare una mostra ai Bagni di Mario di Bologna, una cisterna cinquecentesca ormai asciutta che presenta un panorama desertico un po’ after bomb, proprio in un momento in cui cominciava a circolare sui media la notizia che Marte fosse stato un tempo un pianeta con l’acqua in superficie similmente alla terra, acqua che poi sarebbe in parte evaporata e parte trattenuta da un’enorme area di permafrost esistente in particolare sotto le calotte polari. Se Marte poteva essere un tempo la metafora dell’utopia sociale comunista, oggi, così come Marte si è ridotto a un grande deserto, si è desertificata anch’essa. E questo discorso vale poi in particolare per Bologna, un tempo stella rossa del comunismo italiano, ma oggi ridotta a una zolla arida, come il pianeta rosso. Siamo così giunti al chiarimento delle implicazioni della visione di Marte come metafora politica, ma ci siamo dimenticati di Elon Musk. Elon Musk non può essere di certo annoverato né tra i marziofili marxisti né tra i marziofobi liberisti. Sicuramente è distante anni luce dal marxismo, avendo manifestato simpatie per Trump, anche se sappiamo che Elon Musk come altri miliardari manifesta simpatie per una filosofia nota come longtermism e per il suo ambito di riferimento etico noto come effective altruism. In particolare Musk si interessa all’idea che sul lungo termine la crisi ecologica possa comportare un rischio esistenziale per l’umanità. Ricapitolando, se i decadenti avvertivano l’inquietudine per la caduta della civiltà occidentale sotto la pressione della rivoluzione industriale, se negli anni ’50 e nei decenni a seguire la società di massa manifestava la propria angoscia per la minaccia di un Armageddon nucleare, oggi la situazione non è migliorata. Infatti oggi non c’è solo la paura per la crisi climatica e per l’intelligenza artificiale, ma c’è anche la paura per la fine della civiltà occidentale e infine in tempi recenti si è anche riaffacciata quella per l’ecatombe nucleare. Ora, se non si capiscono le preoccupazioni sulla lunga distanza di tale pensiero non si capiscono le ragioni profonde dell’interesse di Musk per Marte. Musk accoglie varie di queste preoccupazioni anche se non tutte. Si pone quindi il problema di lavorare a un piano di fuga, o quantomeno un piano B per non soccombere a eventuali derive disastrose. Nella letteratura di fantascienza ormai è addirittura divenuta familiare l’idea di grandi navicelle spaziali che solcano lo spazio siderale cariche di esseri umani in ibernazione da risvegliare dopo tempi interstellari. Tuttavia la fantascienza ha rinunciato da tempo a lavorare sull’ipotesi di trasferimenti in massa su pianeti vicini. Anche perché l’esplorazione spaziale ha reso prive di credibilità tutte le ipotesi di pianeti vicini semplicemente abitabili. Nessuno crede più a canali su Marte costruiti dai marziani, anche se non sono del tutto spariti quelli che cercano testimonianze archeologiche di un’antichissima civiltà marziana che sarebbe fuggita da Marte nel momento in cui il pianeta, un tempo blu, ha cominciato a inaridirsi, approdando sulla Terra e dando avvio alla storia umana. Si dice che l’acqua, un tempo abbondante, sia in gran parte evaporata, ma che ce ne sia ancora molta ghiacciata specialmente sotto le calotte polari intrappolata nel permafrost. A questo punto arriva l’idea di Musk che è quella di lanciare delle bombe nucleari ai poli per far sciogliere il ghiaccio sotto i poli e innescare un processo a catena che dovrebbe addirittura riportare un’atmosfera simile a quella terrestre su Marte. Oggi infatti la temperatura è per lo più molto bassa, ma all’equatore essa può raggiungere i 25 gradi celsius durante il giorno e questo significa che, potendo innescare un effetto serra, anche le notti diverrebbero più miti. Insomma, una volta bombardato il pianeta rosso tornerebbe ad essere blu come si immagina che sia stato un tempo. Anche la pressione atmosferica potrebbe innalzarsi pur restando sempre di gran lunga inferiore a quella terrestre. Insomma il sogno di rendere Marte abitabile è molto forte e come nelle strategie di impresa per farlo partire vengono enfatizzate tutte le possibilità positive anche se sono forse insufficienti e scarsamente probabili. Molte volte i progetti tecnologici e scientifici vengono nutriti di aspetti e da spinte emotive finanche inconsce che sono ben lungi dall’essere razionali. Tesla il “mago” dell’elettricità che ha ispirato la visionaria impresa e ascesa di Elon Musk diceva di parlare con i marziani o con i venusiani via radio. Si trattava in realtà molto presumibilmente di un fenomeno di psicofonia, o in inglese EVP che sta per Electronic Voices Phenomena, ben noto agli studiosi del paranormale ma anche agli psichiatri. Tesla condivideva con Hélène Smith l’inclinazione alla pareidolia, che è la tendenza a trovare delle forme nell’informe, o all’apofenia, che è un fenomeno simile, consistente nell’attribuire schemi percettivi noti a elementi casuali, che vanno a costituire connessioni laddove non ce ne sono. Diciamo pure che la pareidolia riguarda più un’inclinazione estetica e l’apofenia un’inclinazione più teoretica, in quanto più rivolta alla gnoseologia. Il punto è che queste non sono solo delle inclinazioni devianti di personalità geniali ma instabili come Nikola Tesla, ma sono degli scantinati della razionalità, in cui essa si mescola all’irrazionale e persino al fantastico se non addirittura al delirio, che costellano la storia del pensiero scientifico, che vale la pena ricordarlo emerge dalle brume dell’astrologia, della magia e dell’alchimia. Se leggiamo i naturalisti rinascimentali come Bernardino Telesio, che sosteneva che la natura andava studiata iuxta propria principia e che parlava pochi decenni prima della comparsa delle teorie di Galileo, capiamo che c’è ancora molto di magico e di alchemico nella sua concezione della natura e la stessa cosa vale per Giordano Bruno, che era coevo di Galilei (vissero per un periodo a pochi chilometri di distanza tanto che potrebbero anche essersi incontrati in quel di Venezia). D’altronde anche Galileo non disdegnava di trarre guadagno dall’attività di astrologo, scrivendo oroscopi a pagamento. Isaac Newton praticava l’alchimia e venne assunto alla zecca di stato come esperto di oro. Ci raccontano che la scienza emerse dalle nebbie di tali dottrine ma poi se ne liberò. Tuttavia la storia della scienza ci racconta un’altra verità: l’irrazionalità non ha mai cessato di tallonare la scienza e di mescolarsi ad essa. Dopo l’alchimia infatti vennero gli studi sull’elettricità. L’elettricità era percepita come una sorta di fluido magico, ora invisibile e ora visibile in fenomeni luminosi, che passava attraverso i corpi. Venivano fatti spettacoli con luminescenze elettriche che avevano del prodigioso fino ad arrivare allo stesso Tesla che si esibiva in performance con luminescenze sul proprio corpo sfruttando fenomeni di induzione elettrica. La personalità stessa di Tesla emerge da questo retroterra culturale di contaminazione e indistinzione tra pratiche scientifiche, prodigi magici e paranormali. Si pensi anche all’idea di riportare in vita corpi morti che sta alla base del Frankenstein di Mary Shelley, e che si basa su teorie in circolazione alla sua epoca. Da questo confine tra scienza e irrazionale emerge anche il cliché dello scienziato pazzo. Ancor più marcatamente questo aspetto si presenta nel caso del magnetismo. Si pensi solo a Franz Anton Mesmer e al mesmerismo che da lui prende il nome e che ebbe una tale diffusione nel mondo dell’occultismo che, ancora nell’Italia del secolo scorso, nelle sedute spiritiche, la medium veniva spesso chiamata “la magnetizzata”. Si dice che Mesmer venne criticato dalla comunità scientifica, tuttavia il mondo naturale ancora nel XIX secolo era percepito come carico di elementi mistici, spirituali e irrazionali che erano stati trattati dai naturalisti del rinascimento. Con il romanticismo si diffuse tra le migliori menti della filosofia tedesca come Schelling e Schopenhauer la Naturphilosophie, che era una filosofia della natura che mescolava istanze scientifiche, spiritualiste e mistiche relativamente alla natura stessa. Infine anche la radioattività si fece strada in mezzo a bizzarre teorie e fascinazioni immaginifiche ad esempio legate all’uso dei raggi X, legate anche in questo caso ad ambienti teosofici. Lo stesso Röntgen chiamo questi raggi “X” perché erano misteriosi e non sapeva come definirli. In conclusione possiamo desumere due discorsi che si intrecciano in questa metafora del bombardamento di marte e della sua immaginosa, ma anche metafisica civiltà, evocata dalle ceramiche, a loro volta riferite ai disegni di Hélène Smith. Il primo ci ricorda che siamo sospesi di fronte alle tematiche della fine, della crisi, dell’apocalisse in una dimensione in cui la scienza non riesce a liberarsi dal suo intreccio con l’irrazionale, la seconda invece più ironica e politica sembra suggerire l’idea che forse anche il pianeta rosso della politica, un tempo ricco di acque e oggi inaridito, abbia bisogno di un bombardamento affinché le sue acque nascoste nei ghiacci possano tornare a portare vita, e per fare ciò serve un atteggiamento medianico e visionario capace di prospettare nuovamente città utopiche, da cui i marziani/marxiani potranno tornare a parlare il loro avveniristico linguaggio. In un certo senso si potrebbe dire “Nuke Marx”, ma non per distruggerlo, bensì, al contrario, per farlo rivivere. Comunque la si pensi l’opera di Marina Gasparini è un’opera che non si limita alle ceramiche, perché queste ceramiche sono come i diodi di una macchina di pensiero carica di input e di considerazioni, che ripropone l’opera nel suo complesso come macchina per pensare o ancora di più per meditare su questi tempi difficili della nostra epoca.

Roberto Terrosi